Infant Meal Pattern Chart Minnesota Department of Children, Families & Learning

Patterns of Nutrient Assistance Programme Participation, Food Insecurity, and Pantry Use amid U.S. Households with Children during the COVID-nineteen Pandemic

1

Department of International Wellness, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 615 N Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Dr. 21205, United states

2

Section of Nutrition and Nutrient Sciences, University of Vermont, 109 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, USA

iii

Food Systems Programme, University of Vermont, 109 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, USA

four

College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, 500 North 3rd Street, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editors: Jose Lara and Jessica C. Kiefte-de Jong

Received: 13 December 2021 / Revised: 23 February 2022 / Accepted: 24 February 2022 / Published: 26 February 2022

Abstract

This study aims to describe differences in participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women and Children (WIC), and school meal programs past household characteristics prior to and during the pandemic, and to examine the association of plan participation with food security condition and food pantry utilize. We analyze secondary data (n = 470) from an online survey collected in July/August 2020 using weighted multiple logistic regression models. Participation in SNAP declined amid households with children in the beginning iv months of the pandemic, while participation in WIC increased slightly, and participation in school meals remained unchanged. At that place were significant differences in SNAP, WIC, and schoolhouse repast programs use by race/ethnicity, income, and urbanicity before and during the pandemic. Food insecurity prevalence was higher amid SNAP participants at both periods but the gap between participants and not-participants was smaller during the pandemic. Pantry use and nutrient insecurity rates were consistently higher amongst federal nutrition assistance program participants, mayhap suggesting unmet food needs. These results highlight the need for increased programme benefits and improved access to nutrient, particularly during periods of hardship.

ane. Introduction

In 2019, prior to the start of the COVID-19 global pandemic, 13.six% of United States (U.South.) households with children (compared to ten.5% of all U.S. households) experienced food insecurity [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted these households as they faced challenges related to the closure of schools and childcare centers, in addition to widespread job losses and reductions to chore-related income [2,3]. Equally a result, the prevalence of food insecurity in households with children was higher during the pandemic compared to all households [4]. Additionally, food insecurity in both households with adults and children has been found to be college in communities of colour due to long-standing structural and systemic inequities [iv,five].

Food insecurity is detrimental to the physical and psycho-social wellness of both children and caregivers [half-dozen,7,8,9]. Children experiencing food insecurity are more likely to have poor nutrition quality [ten], leading to increased run a risk of chronic nutrition-related disease. They also face adverse developmental, social, and academic outcomes, with potential long-term consequences [8,11]. In the U.S., federal food and nutrition assistance programs aim to reduce food insecurity by providing food or benefits for purchasing food. The largest of these programs is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which offers a monthly cash benefit for purchasing foods with the goal of alleviating food insecurity and supporting access to a healthy diet. SNAP is a means-tested program, and households are eligible to receive SNAP benefits if their gross monthly income is at or below 130% of the federal poverty level [12]. Additionally, households may qualify through categorical eligibility if they already receive benefits from other means-tested assistance programs [xiii]. Benefit amounts are calculated based on household income and number of people in the family. During the pandemic, these calculation rules were suspended due to emergency allotments, which raised most households' SNAP benefits to the maximum corporeality [fourteen] However, during the catamenia under consideration, the benefits did not increase for households with the lowest incomes who were already at the maximum amount. These households did non receive additional benefits until the passage of subsequent relief packages [15]. Additionally, during this fourth dimension, income from federal unemployment insurance was counted towards income, which resulted in some participants losing eligibility for SNAP [16]. In response to the pandemic, the U.Southward. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrient and Nutrition Services (FNS) worked with states and retailers to expand the online SNAP purchasing pilot, which was bachelor in 47 states by the end of 2020 [17]. This rapid expansion aimed to provide greater access to food to SNAP participants; however, online redemptions but accounted for 3% of benefits redeemed in December 2020 [17].

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is some other ways-tested program that provides monthly supplemental nutritious food packages to pregnant, lactating, and post-partum individuals, also as infants and children under 5 years [xviii]. WIC eligibility is based on gross income of no more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level or through categorical eligibility. During the pandemic, the USDA granted programmatic waivers that allowed WIC agencies flexibility in implementation for remote certification and enhancement of benefits [19].

School-anile children in low-income households may also receive free or reduced-price nutritious meals through the National School Lunch Plan and School Breakfast Program (hereafter school meals) [20,21]. Children in households with incomes beneath 130 percent of the poverty level or those receiving other federal assistance programs qualify for free meals. Those with family incomes between 130 and 185 percent of the poverty line authorize for reduced-price meals [22]. Additionally, schools and school districts may utilise for the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) if 40% of enrolled children qualify for free- or reduced-price meals through categorical eligibility, which allows all children to receive schoolhouse meals at no cost. In the 2019–2020 school twelvemonth, over xxx,000 schools from all 50 states and the District of Columbia participated in CEP [23]. During the pandemic, public schools were immune to serve gratis take hold of-and-go meals to all children, regardless of eligibility [24].

Participation in federal diet assistance programs has been shown to reduce food insecurity in low-income families [25]. However, numerous barriers prevent some individuals from accessing these programs, including lack of information about the programs, difficulty applying, perception of stigma, and criteria restrictions [26,27,28]. While previous research has shown that participation in federal food and nutrition aid programs increases during periods of economic hardship [29], pandemic-related barriers may accept hampered program participation by some groups [xxx,31]. The use of food banks and pantries also increases in response to unmet food needs, as was evidenced by the long lines outside these facilities nationwide during the pandemic [32]. However, barriers, such as difficulty locating pantries and transportation, or perceived barriers effectually immigration status, hinder individuals' ability to admission pantries, especially those in sure subpopulations [33,34,35].

This paper seeks to better sympathize the use of federal nutrient and nutrition assistance programs amongst households with children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we aim to (i) describe differences in participation in SNAP, WIC, and school meals programs by household characteristics prior to and during the first four months of the pandemic, and (ii) examine the associations of program participation with household nutrient security condition and food pantry use, during both time periods. Nosotros hypothesize that at that place are socio-demographic differences in program participation and that, after adjusting for income and other key covariates, respondents participating in federal nutrition help programs are less likely to experience nutrient insecurity and less probable to use food pantries compared to non-program participants.

2. Materials and Methods

ii.1. Sample Population

We surveyed 1510 U.S. adults in July/Baronial 2020 using Qualtrics (Provo, UT, UsaA.) online panels. Survey participants were selected from 2 online panels conducted in parallel: the first panel was representative of the U.S. adult population based on the 2018 American Community Survey data (five-yr estimates) for race/ethnicity (hereafter race) and age, while the second was representative for race but lower-income households (i.eastward., with an annual household income in 2019 less than USD 50,000) were oversampled. The response rates of x.4% and 27.0% were calculated for the national sample and low-income sample, respectively, using the American Association for Public Opinion Research'south figurer for spider web-based surveys (Response Rate 4) [36,37]. For the electric current analysis, which focuses on respondents in households with children, survey weights were calculated using income data for households with children from the 2019 national Demography [38], and then that results may be generalized to reflect the national income distribution of households with children.

2.2. Variables and Measures

The survey asked participants to answer questions on a variety of topics, including food security, food admission, and food assistance program participation, as well as household and private demographic characteristics. The catamenia from March 2019 to 10 March 2020 was referred to equally "prior to the pandemic", while the period from 11 March 2020 to the time of the survey (covering approximately iv months) was referred to as "since the onset of the pandemic". The average time for completing the survey was 23 min. Fifty-seven percent of respondents identified as female person, and respondent age was distributed equally across 3 age groups: 18–34, 35–54, and 55+. Respondents in the analytical sample, described below, represented 47 states in the U.Due south. plus the District of Columbia.

The key variables in our assay reflected use of federal nutrition and nutrient assistance programs, specifically SNAP, WIC, and school meals. Respondents were asked to betoken which programs (i.e., SNAP, WIC, and school meals), if any, they used the year prior to and since the onset of the pandemic. Each federal plan variable in the assay indicates whether a respondent used the plan, either independently or in conjunction with another program. For example, those counted in the SNAP category may take either only used SNAP or may have used SNAP in addition to WIC and/or school meals. The other two cardinal variables in our assay were food pantry use, as an indicator of unmet food needs, and food security status. Food security was measured using the USDA six-item module [39], in which respondents who say "aye" to two or more than of the six questions are categorized equally experiencing food insecurity. Food pantry utilise was measured past asking respondents if they used food pantries/nutrient banks in the 12 months prior to the pandemic and since the onset of the pandemic.

Demographic variables collected in the survey and explored in the analysis included (ane) household annual income in 2019 with half dozen response categories that were regrouped into three for analysis: less than USD 50,000, USD 50,000–99,000, and greater than USD 100,000; (2) race/ethnicity, dichotomized as not-Hispanic white and not-white due to sample size limitations; (3) number of children in the household, dichotomized as one kid versus more than one child; (4) urbanicity, captured using participant zip lawmaking of residence and categorized as rural and urban based on the nomenclature arrangement from the Rural Health Enquiry Centre [40]; and (5) U.Southward. Census region adamant based on respondent state of residence [41]. The parent survey collected more than granular data on race/ethnicity, just we were unable to disaggregate data in this secondary analysis due to sample size limitations. Additionally, in the current sample (of households with children), less than iv% of households reported four or more children. Almost all households reported one or 2 children, with ~ten% of households reporting three children. Because of this considerable skewness in the distribution, the variable for number of children was dichotomized. To double check that this would not affect the results, a sensitivity assay was run for the models presented, using number of children every bit a continuous variable. This did not essentially change whatever of the estimated coefficients or their standard errors, (all changes were approximately ±1%). Large rural, pocket-sized rural, and isolated categories were combined into ane rural category due to sample size limitations.

2.3. Analysis

Analyses were limited to 470 households with children under the age of xviii that had consummate data for all relevant variables. Analyses were conducted in STATA 15, two-tailed p-values were used for all analyses, and statistical tests were considered significant at p-values less than 0.05. First, weighted distributions of variables were examined. Next, weighted logit multivariate models were used along with the "margins" command to calculate adjusted prevalence of SNAP, WIC, and schoolhouse meals participation (overall and by household demographic characteristics) for the two time periods examined. These models included race, income category, number of children under 18 years of age, U.S. region, and urbanicity.

Lastly, a second gear up of multivariate logit regression analyses were used to exam the association of programme participation with two outcome variables—food insecurity and pantry utilize. These models included all three programs—SNAP, WIC, and schoolhouse meals— equally iii separate binary variables, were adjusted for all covariates listed in a higher place, and were run for the ii time periods analyzed, the year prior to the pandemic and the start four months of the pandemic. Based on these models, adjusted prevalence and 95% conviction intervals were calculated for each outcome both prior to and during the start four months of the pandemic.

3. Results

iii.i. Description of Programme Participants

Table 1 presents a description of the sample. Of the 470 respondents, the majority were white (73.2%), living in an urban surface area (90.2%), and with a household income over USD 100,000 (61.2%). About a quarter of respondents had a household income of USD fifty,000–99,000 (27.two%) and 11.6% had a household income of less than USD 50,000. More than than one-third of respondents were from the Southern Census regions (39.0%), most a quarter were from the Northeast (26.0%), and xiv.4% and 20.6% were from the Midwest and West, respectively. In the 12 months prior to the pandemic, 37.4% of the households with children participated in SNAP compared to only 27.eight% during the showtime four months of the pandemic. For WIC, 19.4% of households with children participated in the twelvemonth prior to the pandemic compared to 24.3% during the first four months of the pandemic. For school meals, 24.7% participated prior to the pandemic compared to 22.8% during the first iv months. A total of 22% and 28.8% of participants received food from food pantries prior to and during the first 4 months of the pandemic, respectively. Food insecurity rates increased from 38.7% to 51.8% over the two time periods under investigation.

3.two. Differences in Program Participation past Household Characteristics

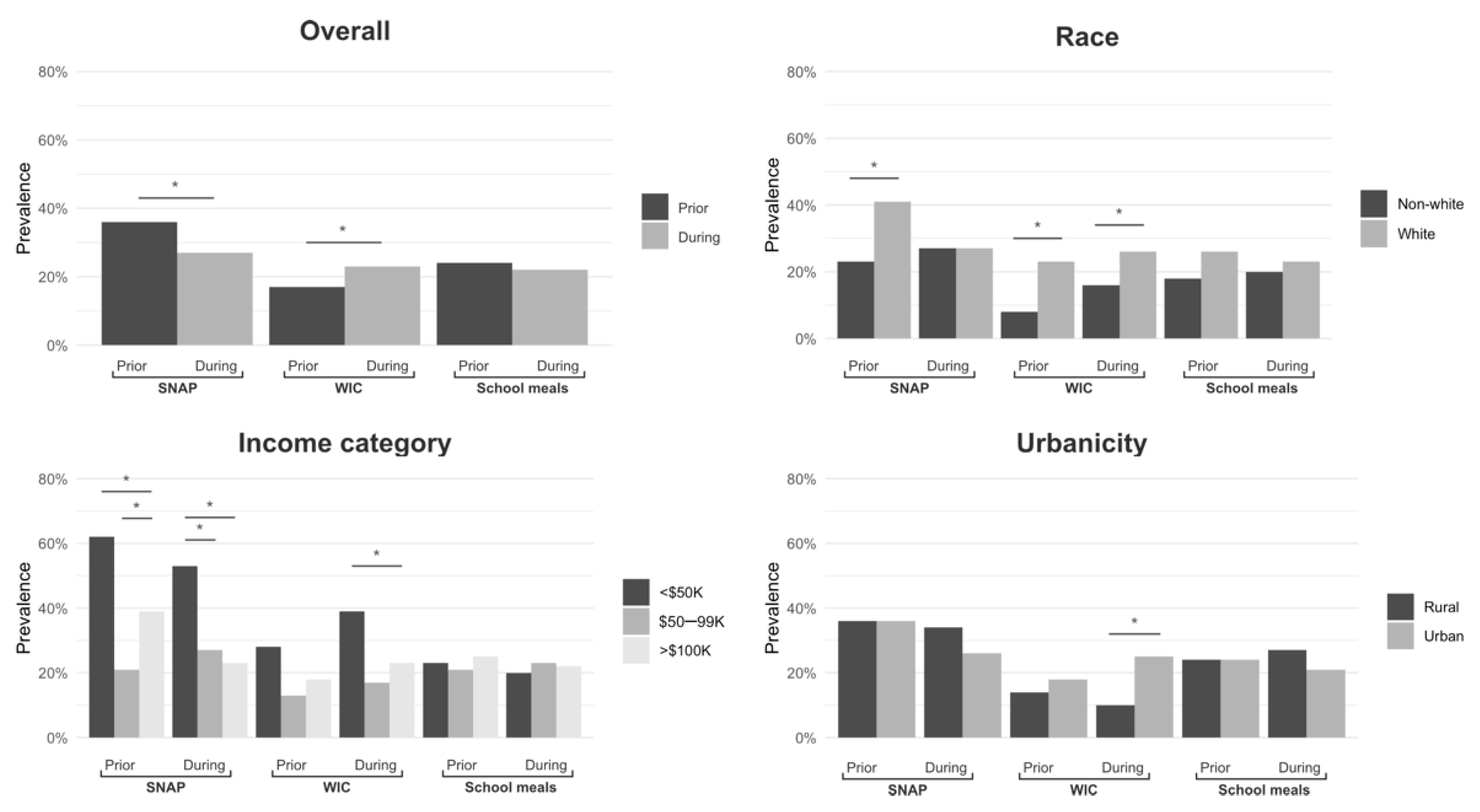

Based on the results from the first ready of multivariate models, the adjusted program participation rates—overall and by cardinal household demographic characteristics—are presented in Figure one. Overall, respondents were more than likely to use SNAP the year prior to the pandemic than during the first four months of the pandemic. Conversely, respondents were less probable to apply WIC prior to the pandemic compared to the showtime 4 months. There were no meaning differences in overall school meal participation between the ii time periods.

White participants were more likely to use SNAP prior to the pandemic compared to not-white participants and were as well more probable to utilise WIC during both time periods. Those in urban areas were likewise more than likely to use WIC during the pandemic than those in rural areas. Participants in the lowest income categories (<USD 50,000) were more likely to apply SNAP during both time periods and WIC during the pandemic compared to those in the middle (USD 50,000–99,000) and highest (>USD 100,000) income categories.

3.3. Association of Food Insecurity and Pantry Utilize with Program Participation

Based on the second gear up of multivariate analyses, 36.viii% and 53.0% of households with children experienced nutrient insecurity in the 12 months prior to and during the first four months of the pandemic, respectively. The adapted prevalence of food insecurity by programme participation is presented in Table 2. Both prior to and since the onset of the pandemic, households using SNAP were significantly more than likely to feel nutrient insecurity compared to households not using SNAP. There was no deviation in the prevalence of food insecurity by WIC and school meals participation status prior to the pandemic. Still, during the first iv months of the pandemic, households using WIC and school meals were significantly more likely to feel food insecurity compared to those not using the programs.

The adjusted prevalence of food pantry use by program participation is presented in Table 3. Overall, 16.7% and 24.9% of respondents used food pantries prior to and during the first iv months of the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, households using SNAP, WIC, and school meals were more probable to use food pantries compared to households not using the programs. Similarly, during the commencement four months of the pandemic, households using SNAP and WIC were significantly more probable to use food pantries compared to those not using the programs.

iv. Word

In this sample of households with children, we (ane) examined the use of federal food and nutrition assist programs in the year prior to and during the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic by household characteristics, and (ii) assessed the clan of plan participation with food insecurity and food pantry apply. Every bit hypothesized, we found significant differences in the use of SNAP, WIC, and school meal programs by race, income, and urbanicity before the pandemic; virtually of these differences persisted or were exacerbated in the months following the pandemic. Overall, compared to the year before the pandemic, SNAP participation declined among households with children in the outset four months of the pandemic, while WIC participation increased slightly, and school meal participation remained unchanged.

Like declines in SNAP participation amidst vulnerable households in the months following the onset of the pandemic take been observed by others [30,42]. During the pandemic, initial SNAP policies that counted boosted sources of benefits (e.g., unemployment insurance) towards household income may take made some households with children ineligible. Ettinger de Cuba and colleagues (2019) found that SNAP benefit reductions and cutoff during economic hardship were a barrier to SNAP participation amid households with children and that such reduction was associated with greater odds of poor health outcomes [43]. Further, while USDA SNAP waivers designed to facilitate enrollment were implemented early in the pandemic, engineering science demands and lack of transportation may have contributed to lower participation rates among some households with children [44]. A Utah-based report found that SNAP-eligible respondents experienced travel-related barriers to SNAP certification and recertification during a similar time period in 2020 [45].

National data reflect inconsistent shifts in WIC participation [46]; 26 states and the District of Columbia reported an increase or no change, and 24 states reported a decline in participation. In the current study, rural and urban households reported participating in WIC at similar rates in the twelvemonth prior to the pandemic, but in the month following the get-go of the pandemic, significantly fewer rural households participated in WIC. Rural areas in the U.S. experience higher rates of poverty and accept been shown to experience more challenges to WIC participation in pre-COVID-19 times [47]; these challenges may have heightened during the pandemic, resulting in lower rates of participation.

Prior to the pandemic, SNAP and WIC participation rates were higher amongst white households in this report. In the first few months of the pandemic, the rates became somewhat more equitable, but for different reasons. Fewer white households participated in SNAP in the start four months of the pandemic, while more not-white households participated in WIC. These disparate trends by geography and race call for investigating strategies and waivers that may be necessary for reaching different populations in periods of emergency.

Contrary to our hypothesis, in regression models adjusting for income and other covariates, food insecurity and food pantry apply were significantly higher for SNAP users compared to non-SNAP users, both prior to and during the outset four months of the pandemic. Examining the coefficients and conviction intervals for the 2 models for SNAP participation at these two points, nosotros also note that, although the prevalence of food insecurity increased amid all households, the increase was less pronounced amid SNAP households (4.five percentage points) compared to that for non-SNAP households (23.vi per centum points). We saw a similar pattern in nutrient pantry use, where pantry use increased by 3.5 percentage points among SNAP users compared to 10.7 percentage points among not-SNAP users. However, since separate models were estimated for SNAP (and nutrient pantry) apply for periods prior to and during the pandemic, statistical comparisons of coefficients across models was not feasible. These findings advise that households receiving SNAP benefits, though already experiencing higher rates of nutrient insecurity and pantry employ, may have been less probable to see a further exacerbation of their unmet needs during the pandemic, compared to not-SNAP households for whom we observed more pronounced changes in both nutrient insecurity and pantry employ during the kickoff 4 months of the pandemic. These are of import findings as they highlight the protective effect of SNAP participation during emergencies, and therefore the need to ensure the acceptable attain of the plan during such difficult times. WIC and school meals likewise showed differential patterns of food insecurity and pantry utilize among participants and not-participants. The considerable increase in nutrient pantry utilize observed among households that did non participate in SNAP could exist the result of unmet food needs experienced past these households). However, it could also bespeak that, during the showtime four months of the pandemic, a greater number of disadvantaged households experienced barriers in accessing SNAP and thus had to resort to food pantries. This interpretation is in line with the results from a recent study, which found that SNAP participation amid the most vulnerable—defined as low-income, food insecure—households declined during the first months of the pandemic [48].

A unlike pattern was observed for WIC, where both food insecurity and pantry employ almost doubled amid participating households, with much smaller increases observed among non-participating households. While WIC participation has consistently shown benefits to participants and their families in terms of improved nutrition quality [49], the lower amount of overall benefits and the challenges to obtain WIC-approved items during the pandemic may have contributed to higher unmet needs amid participating households.

4.1. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. The data collected were cross-sectional and therefore we cannot appraise the temporality of the clan between food insecurity and program participation. For instance, the college food insecurity rates amid SNAP participants both prior to and during the first 4 months of the pandemic likely derive from the fact that households experiencing food insecurity are more likely to become SNAP recipients. The extent of this self-selection, which likewise applies to the other programs, is unknown in the current data. Still, it is likely that information technology occurred similarly across the 2 time periods. Therefore, our comparisons of nutrient insecurity rates and pantry use prevalence beyond the two time periods based on program participation status remain valid. Although recent examinations of online panels accept been shown to be apparent sources for collecting data [l], data nerveless from online panels may underrepresent those with low literacy, disability to take surveys in English/Spanish, or those without cell phones or access to the Net. The data collected from the parent survey were representative of the U.S. population past race and income. Nonetheless, because this secondary assay used only a subset of data from the parent survey, our analysis was not nationally representative, and the results of this written report may not be generalizable to the entire U.S. population of households with children. The parent survey also did not collect data on citizenship or whether respondents were born outside the U.S.

Additionally, the prevalence of nutrient insecurity found in this study is substantially higher than the prevalence documented by the USDA [51]. Ane possible explanation of this may be timing of data drove; we collected data in the first four months of the pandemic, while the USDA nerveless information in December 2020, after many people received stimulus checks and other federal benefits, or later some people may have returned to work. Another limitation of this study is that plan participation was self-reported and open to social desirability and recall bias. Think bias is of particular business concern given that the survey asked about 2 periods at one point in time. Social desirability bias would likely occur for both fourth dimension points recalled, and therefore, would not affect the comparisons in participation over fourth dimension. Information technology is besides important to note that, although program participation prior to the pandemic referred to a 12-month menstruation, program participation since the onset of the pandemic just covered a four-month period. This may take contributed to underestimate the rates of participation during the first four months of the pandemic. Finally, the USDA six-detail food insecurity module does not explicitly ask food security questions nearly children in the household just was chosen to lower respondent burden; inquiry shows that household food insecurity prevalence estimates differ simply minimally from those derived from the xviii- or the ten-item modules [39].

4.2. Public Health Implications

Our findings bear witness that participation in 3 of the largest federal nutrition assistance programs was associated with significantly higher prevalence of food insecurity and food pantry use, both in the twelvemonth prior and in the months following the pandemic. One potential explanation is that, while these programs have of import benefits, they are not adequate to meet household needs, especially during emergencies. Prior enquiry has shown that households in greater demand and with limited access to food tend to utilize safety net programs more ofttimes, and that food insecurity persists amongst many participating households [1,6]. Thus, while the USDA's means-tested food assistance programs strive to assistance eligible households encounter their needs, participants may still rely on the charitable nutrient organization to fulfill the unmet needs during emergencies, in times of hardship or, in many instances, chronically [52,53]. Unlike SNAP, WIC, and school repast programs, which have income eligibility requirements, food pantries are usually accessible to all households. Food banks and pantries are disquisitional to providing immediate solutions to severe food deprivation; thus, an increase in nutrient pantry apply is a useful indicator of unmet food needs in the customs.

Writer Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and P.O.-5.; Information curation, M.H. and F.A.; Formal assay, Chiliad.H. and F.A.; Funding acquisition, F.A. and P.O.-V.; Investigation, K.H., E.H.B., F.A., F.B. and P.O.-V.; Methodology, K.H., F.A. and P.O.-V.; Project administration, P.O.-V.; Supervision, P.O.-Five.; Visualization, Thousand.H.; Writing—original draft, K.H., E.H.B., F.B. and P.O.-V.; Writing—review and editing, K.H., Eastward.H.B., F.A., F.B. and P.O.-V. All authors accept read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a COVID-19 seed grant from the College of Wellness Solutions, Arizona Country University's and past the university's Investigator Research Funds. Additionally, this research was supported by a Directed Research grant from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. The study sponsors had no role in study design, implementation, assay, or write-up.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The written report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of New Mexico State Academy's Role of Research Integrity and Ethics (#20024). IRB exemption from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (#2359).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Information Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This research is conducted as office of the National Nutrient Access and COVID Enquiry Team (NFACT). NFACT is a national collaboration of researchers committed to rigorous, comparative, and timely nutrient admission research during the fourth dimension of COVID-xix. We do this through collaborative, open up admission research that prioritizes advice to key decision-makers while building our scientific understanding of food organisation behaviors and policies. To larn more visit www.nfactresearch.org (Accessed on 1 June 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2019; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, U.s.a., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karpman, Chiliad.; Zuckerman, S.; Gonzalez, D.; Kenney, G.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Straining Families' Abilities to Afford Basic Needs: Depression-Income and Hispanic Families the Hardest Hit; Urban Found: Washington, DC, United states, 2020; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Montenovo, L.; Jiang, Ten.; Rojas, F.L.; Schmutte, I.M.; Simon, One thousand.I.; Weinberg, B.A.; Wing, C. Determinants of Disparities in Covid-19 Task Losses; Working Newspaper Series; National Bureau of Economic Enquiry: Cambridge, MA, U.s.a., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, Due north.; Ali, South.H.; O'Connor, J.; Tozan, Y.; Jones, A.M.; Capasso, A.; Foreman, J.; DiClemente, R.J. Nutrient Insecurity among Households with Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from a Written report among Social Media Users across the The states. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, J.N. COVID-19'south Disproportionate Impact on Communities of Colour Spotlights the Nation'southward Systemic Inequities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2020, 26, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Nutrient Insecurity And Wellness Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, C.; Field, Southward.; Honikman, S. Food Insecurity, Maternal Mental Health, and Domestic Violence: A Call for a Syndemic Approach to Research and Interventions. Matern. Child Health J. 2020, 24, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drennen, C.R.; Coleman, Southward.M.; de Cuba, S.E.; Frank, D.A.; Chilton, M.; Melt, J.T.; Cutts, D.B.; Heeren, T.; Casey, P.H.; Black, G.M. Nutrient Insecurity, Wellness, and Development in Children Under Age Four Years. Pediatrics 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallegos, D.; Eivers, A.; Sondergeld, P.; Pattinson, C. Nutrient Insecurity and Child Development: A Country-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, M.J.; van den Berg, A.Due east.; Asigbee, F.M.; Vandyousefi, S.; Ghaddar, R.; Davis, J.Due north. Child-Study of Nutrient Insecurity Is Associated with Diet Quality in Children. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althoff, R.R.; Ametti, M.; Bertmann, F. The Part of Food Insecurity in Developmental Psychopathology. Prev. Med. 2016, 92, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities a Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits. Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/inquiry/nutrient-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Falk, Yard.; Aussenberg, R.A. The Supplemental Nutrition Aid Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- USDA FNS USDA Increases Emergency SNAP Benefits for 25 Meg Americans. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/usda-006421 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Center on Upkeep and Policy Priorities USDA, States Must Act Swiftly to Evangelize Food Assistance Allowed by Families Outset Act; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Center on Upkeep and Policy Priorities Pandemic Unemployment Insurance Provisions: What They Mean for Access to SNAP, Medicaid, and TANF. Available online: https://world wide web.cbpp.org/research/economy/pandemic-unemployment-insurance-provisions-what-they-mean-for-access-to-snap (accessed on 10 Feb 2022).

- Jones, J.Due west. Online Supplemental Nutrition Aid Programme (SNAP) Purchasing Grew Substantially in 2020. U. Southward. Dep. Agric. Econ. Res. Serv. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2021/july/online-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap-purchasing-grew-substantially-in-2020/ (accessed on vii Feb 2022).

- USDA ERS WIC Participation Vicious past 30 Percentage between Fiscal Years 2010 and 2019. Bachelor online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=99747 (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Usa Section of Agronomics Nutrient and Diet Services. Changes in USDA Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Operations During the COVID-nineteen Pandemic: A First Look at the Bear upon of Federal Waivers; United states of america Section of Agriculture: Washington, DC, The states, 2021; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- USDA FNS Kid Nutrition Tables. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/kid-nutrition-tables (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- USDA FNS WIC Data Tables. Available online: https://world wide web.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program (accessed on six September 2021).

- Feeding America National Schoolhouse Lunch Program (NSLP). Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/accept-action/advocate/federal-hunger-relief-programs/national-school-lunch-programme (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- FRAC. Community Eligibility Report: The Key to Hunger-Free Schools. Schoolhouse Year 2019–2020; Food Research & Action Center: Washington, DC, U.s.a., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Section of Agronomics Schoolhouse Meals. Bachelor online: https://www.usda.gov/coronavirus/schoolhouse-meals (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Ralston, Chiliad.; Treen, 1000.; Coleman-Jensen, A.; Guthrie, J. Children'south Food Security and USDA Child Nutrition Programs; Economic Information Message Number 174; USDA Economical Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- McAleer, E.; Siller, L.; Greenhalgh, E.; Avila, G.; Searles, R.; Burns, M.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Cluggish, S.; Lemmerman, J.; Minc, Fifty. Barriers to SNAP; Project Bread: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient Research & Activity Centre. Barriers That Forbid Depression-Income People from Gaining Access to Food and Diet Programs; Nutrient Research & Action Center: Washington, DC, The states, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balasuriya, L.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Seligman, H.One thousand. Federal Nutrition Programs later on the Pandemic: Learning from P-EBT and SNAP to Create the Next Generation of Nutrient Condom Net Programs. J. Wellness Intendance Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, D. SNAP Is Constructive and Efficient. Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/snap-is-effective-and-efficient (accessed on nineteen October 2021).

- Fang, D.; Thomsen, One thousand.R.; Nayga, R.M.; Yang, W. Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from a Survey of Depression-Income Americans. Food Secur. 2021, 14, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, S.One thousand.; Cantor, J.; Dastidar, M.G.; Beckman, R.; Richardson, A.S.; Baird, 1000.D.; Dubowitz, T. SNAP Participants and High Levels of Food Insecurity in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konish, L. "This Can't Expect". Why Long Food Lines Indicate Need for More Coronavirus Stimulus Assist; CNBC: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, U.s.a., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grier-Welch, A.; Marquis, J.; Spence, M.; Kavanagh, Thousand.; Anderson Steeves, E.T. Food Acquisition Behaviors and Perceptions of Food Pantry Use among Food Pantry Clients in Rural Appalachia. Ecol. Nutrient Nutr. 2021, 60, seventy–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.Due east.; Lucero, J.; Crosbie, E. "It's Nice to Have a Niggling Flake of Habitation, Even If It's Just on Your Plate"–Perceived Barriers for Latinos Accessing Food Pantries. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Alexander, T.; Slaughter-Acey, J.C.; Berge, J.; Widome, R.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Barriers to Accessing Healthy Food and Food Help During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Racial Justice Uprisings: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Emerging Adults' Experiences. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1679–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research Report on Online Panels—AAPOR. Available online: https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/Reports/Report-on-Online-Panels.aspx (accessed on 13 Feb 2022).

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rates—An Overview—AAPOR. Available online: https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- US Census Bureau Family Income: FINC-01. Selected Characteristics of Families by Full Money Income. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-finc/finc-01.html (accessed on half-dozen September 2021).

- USDA ERS U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-help/food-security-in-the-u-due south/survey-tools/#six (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Rural Health Inquiry Centers. Bachelor online: https://www.ruralhealthresearch.org/centers (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- U.Southward. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Assistants-Geography Division US Census Regions No Engagement. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Dubowitz, T.; Dastidar, Thou.Yard.; Troxel, Due west.M.; Beckman, R.; Nugroho, A.; Siddiqi, Southward.; Cantor, J.; Baird, Yard.; Richardson, A.S.; Hunter, Chiliad.P.; et al. Food Insecurity in a Low-Income, Predominantly African American Cohort Following the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger de Republic of cuba, Due south.; Chilton, M.; Bovell-Ammon, A.; Knowles, M.; Coleman, S.M.; Black, M.M.; Cook, J.T.; Cutts, D.B.; Casey, P.H.; Heeren, T.C.; et al. Loss Of SNAP Is Associated With Food Insecurity And Poor Health In Working Families With Young Children. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Acciai, F.; Martinelli, Southward.; Harper, K.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Neff, R.; Niles, M.T. Nutrient Assistance Programme Participation among Us Household during COVID-19 Pandemic. ASU Food Policy Environ. Res. Group 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.internet/2286/R.ii.N.244 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Voorhees, K.; Savoie-Roskos, M.; Coombs, C.; LeBlanc, H.; Wengreen, H. P36 The Impact of COVID-xix on Food Security Condition and Food Access Amidst SNAP-Eligible Utahns. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, S40–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.; Neuberger, Z. Eligible Low-Income Children Missing Out on Crucial WIC Benefits During Pandemic. Available online: https://world wide web.cbpp.org/research/food-help/eligible-depression-income-children-missing-out-on-crucial-wic-benefits-during (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Isaacs, South.; Shriver, 50.; Haldeman, L. Qualitative Analysis of Maternal Barriers and Perceptions to Participation in a Federal Supplemental Diet Program in Rural Appalachian North Carolina. J. Appalach. Health 2020, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Acciai, F.; DeWeese, R.S. SNAP Participation amidst Low-Income US Households Stays Stagnant While Food Insecurity Escalates in the Months Post-obit the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steeves, Due south.; Acciai, F.; Tasevska, N.; DeWeese, R.Due south.; Yedidia, M.J.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children Spillover Effect: Practise Siblings Reap the Benefits? J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.L.; Seibert, Southward.E.; Goering, D.; O'Boyle, E.H., Jr. A Tale of 2 Sample Sources: Do Results from Online Panel Data and Conventional Data Converge? J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, 1000.P.; Gregoery, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the Us in 2020; Economic Research Service, US. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, U.s.a., 2021; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Mabli, J.; Worthington, J. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Emergency Food Pantry Apply. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 647–656.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosler, A.S.; Cong, 10.; Alharthy, A. Nutrient Pantry Use and Its Association with Food Environs and Food Conquering Behavior among Urban Adults. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. Adjusted prevalence for SNAP, WIC, and school meals participation in the 12 months prior to the pandemic by household demographic characteristics. Asterisks stand for statistically significant differences. Abbreviations: Supplemental Nutrition Help Program (SNAP); Special Supplemental Nutrition Programme for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Figure i. Adjusted prevalence for SNAP, WIC, and school meals participation in the 12 months prior to the pandemic by household demographic characteristics. Asterisks correspond statistically significant differences. Abbreviations: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Tabular array 1. Demographic characteristics of households with children prior to and during the first 4 months of the pandemic (north = 470).

Table ane. Demographic characteristics of households with children prior to and during the first four months of the pandemic (n = 470).

| Sample Characteristics | % (n = 470) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity a | |

| Hispanic | 13.viii |

| Not-Hispanic White | 73.2 |

| Not-Hispanic Black | 8.half-dozen |

| Asian | 3.one |

| Native American | 0.3 |

| Multiple Races | 1 |

| Income | |

| <USD l,000 | 11.half-dozen |

| USD 50,000–99,000 | 27.two |

| >USD 100,000 | 61.2 |

| % households with multiple children (<18 years of historic period) | 58.5 |

| Urbanicity (% urban) | 90.two |

| U.S. Census Region | |

| Northeast | 26 |

| Midwest | 14.4 |

| South | 39 |

| West | xx.6 |

| Nutrient pantry use | |

| Prior to the pandemic | 22.7 |

| First four months of the pandemic | 28.3 |

| Nutrient insecurity | |

| Prior to the pandemic | 38.7 |

| First four months of the pandemic | 51.viii |

Table two. Adjusted prevalence of nutrient insecurity amid households with children by federal food assistance programme participation status prior to and during the first four months of the pandemic.

Tabular array 2. Adjusted prevalence of food insecurity among households with children by federal nutrient assistance programme participation status prior to and during the start 4 months of the pandemic.

| % Food Insecurity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | During | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |||

| Overall | 36.8 | 31.9, 41.6 | - | 53.0 | 47.9, 58.1 | - |

| SNAP | ||||||

| No | 23.7 | 18.3, 29.1 | <0.01 | 47.3 | 41.6, 53.1 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 62.5 | 54.4, seventy.five | 67.0 | 57.4, 76.6 | ||

| WIC | ||||||

| No | 36.1 | 30.8, 41.iv | 0.63 | 45.viii | forty.three, 51.2 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 39.7 | 26.5, 52.8 | 73.5 | 64.1, 83.0 | ||

| Schoolhouse Meals | ||||||

| No | 34.5 | 29.2, 39.8 | 0.14 | 48.9 | 43.3, 54.5 | 0.01 |

| Yep | 44.ane | 32.2, 56.0 | 66.2 | 54.9, 77.five | ||

Table 3. Adjusted prevalence of food pantry use amongst households with children by federal food help programme participation status prior to and during the first four months of the pandemic.

Table 3. Adjusted prevalence of food pantry utilize among households with children past federal nutrient assistance program participation status prior to and during the first 4 months of the pandemic.

| % Food Pantry Use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | During | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |||

| Overall | 16.vii | 12.7, 20.vii | 24.9 | 20.6, 29.2 | ||

| SNAP | ||||||

| No | 10.4 | 6.six, 14.2 | <0.01 | 21.1 | 16.3, 25.8 | <0.01 |

| Yep | 33.4 | 23.5, 43.4 | 36.9 | 26.eight, 47.0 | ||

| WIC | ||||||

| No | fourteen.4 | 10.4, 18.4 | <0.01 | 18.3 | 14.2, 22.4 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 29.five | 18.2, 40.eight | 53.2 | 42.2, 64.1 | ||

| School Meals | ||||||

| No | 13.1 | ix.two, sixteen.9 | <0.01 | 22.6 | 18.0, 27.2 | 0.05 |

| Yeah | 32.7 | 21.9, 43.five | 34.0 | 22.8, 45.two | ||

| Publisher's Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open admission commodity distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/5/988/htm

,

,