Nursing Diagnoses for Family Who Lost a Loved One

Grief is a normal and expected reaction to loss. Anticipatory grief is an emotional response that is experienced before a true loss. Other terms for this prescient state include preparatory grief or premature grief. This specific subset of grief is an unconscious procedure that happens when stability is threatened, nearly often by a new and unwelcomed diagnosis.1 Anticipatory grief encompasses the mourning, coping, and planning of one'south life in response to an impending loss too every bit futurity losses.2 Every bit losses of identity, part, and potentially loss of life accumulate along the illness trajectory, anticipatory grief processes continue to be triggered; the result is often an overwhelming cumulative loss effect.1 Palliative intendance nurses are uniquely positioned to screen and care for anticipatory grief. This article aims to review tools and strategies to raise the care of patients and caregivers suffering from anticipatory grief. As seen in the post-obit instance report, interpreting a patient'due south emotional country is integral to providing the best intendance possible.

Example STUDY

Mrs Jones is a 42-year-old adult female with metastatic breast cancer who has undergone a bilateral mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiations. She is now hospitalized for new onset of severe headaches. She is well known to the palliative care team from her prior hospitalizations related to treatment complications and uncontrolled symptoms. She has a devoted husband and 2 children, aged 10 and 12 years. During past interactions, she has been vibrant, pleasant, and tolerant of the many burdens of her disease and handling. Mrs Jones' oncologist discusses a new finding of brain metastasis and the lack of farther chemotherapy options available so leaves the room. Mary, the palliative intendance nurse, enters Mrs Jones' room to find her crying and slightly withdrawn, no longer at her measured baseline. What assessment tools and strategies practise nurses have to address the potential range of emotions during this interaction?

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Nursing theories help to frame, explain, or define the provision of nursing. In the Roy Adaptation Model of Nursing, Dr Callista Roy3 conceptualizes the person from a holistic perspective. Roy'southward model focuses on the interrelated biological, psychological, and social systems. Individuals strive to maintain a balance between these systems and the exterior world with the goal of achieving an adequate level of coping. Persons with serious illness face numerous stressors in their environment to which a coping response (either adaptive or maladaptive) is forced. This model consists of the following domain concepts: person, health, environment, and nursing. Nursing's goal is the promotion of adaptation in all 4 modes (physiological, self-concept, role function, and interdependence), thereby influencing the person'southward health, quality of life, and dying with dignity.3

Anticipatory grief for persons with serious illness and their family members could pose a threat to their integrity and demand adaptation if integrity is to be maintained. The goal of nursing is to help promote adaptation during health and affliction. Utilizing Roy's Adaptation Model of Nursing aids nurses in facilitating positive adaptation of seriously ill patients and their families equally they cope with anticipatory grief, loss in multiple domains, and acceptance of limited prognosis, thus assuasive for quality of life and a dignified decease.3

DEFINITION OF ANTICIPATORY GRIEF

Anticipatory grief is "described equally a range of intensified emotional responses that may include separation anxiety, existential aloneness, deprival, sadness, thwarting, anger, resentment, guilt, exhaustion, and desperation."4 Anticipatory grief can be a response to the loss of function, loss of identity, and changes in part, in addition to impending death.4 Furthermore, anticipatory grief is experienced not only by the terminally ill person but also by family, friends, and caregivers.

A patient who has just received difficult news about her cancer may begin to testify signs of anticipatory grief. Symptoms can span physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual domains. These symptoms tin be experienced by both the patient and family. Examples of physical symptoms are similar to those experienced by loved ones after the anticipated death, that is, sleep and ambition disturbance, headache, nausea, and fatigue. Other individuals may feel broken-hearted, sad, helpless, disorganized, forgetful, or angry. Doubting i's religion or questioning the being of God is not unusual. Overall, people may besides notice difficulty in connecting emotionally with others.iv

Unfortunately, anticipatory grief rarely eliminates or ameliorates the grief i experiences afterward the actual expiry. Still, the experience of anticipatory grief can be benign in that i has time to prepare and develop coping skills for the inevitable changes to come.5 As palliative care and hospice providers, information technology is essential that we place patients and families experiencing anticipatory grief in order to assess for complications, provide support, and nurture effective interventions to aid in coping.

ASSESSMENT OF ANTICIPATORY GRIEF

Evaluating for anticipatory grief involves an initial assessment of depression and feet in patients and family members.6 Symptoms of depression and anxiety may increase in patients with terminal illnesses and their families and can contribute to the suffering experienced.6 Identifying clinical levels of low and feet beyond generalized sorrow tin be challenging for clinicians. Useful tools for performing this important evaluation include the Hospital Feet and Depression Calibration, the Geriatric Low Scale, or the Beck Depression Inventory.7 These tools have been validated to be effective in the screening for psychiatric conditions in patients with avant-garde illness. These tools involve cocky-screening questionnaires, ranging from 14 to 21 questions that can be used to chop-chop identify depression and anxiety in these seriously sick patients.

A complete symptom assessment follows the mental health evaluation. Symptom management is paramount equally uncontrolled symptoms such every bit pain and dyspnea tin can exacerbate existential sources of suffering. In addition, uncontrolled symptoms tin can increment the suffering of the family members who are witness to the patient's distress.vii In one case a general evaluation is complete and symptom control is optimized, the nurse can continue the cess for anticipatory grief.

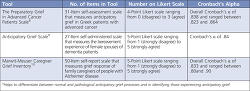

The anticipatory grief tools that tin be utilized with patients and family members are the Preparatory Grief in Advanced Cancer Patients Scale (PGAC), Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS), and the Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory (Table 1). The PGAC is a 31-item cocky-assessment scale developed to measure anticipatory grief responses within a singular population. The reliability and validity of the PGAC tool take been established, and it was too accounted acceptable by the population studied, which included Greek patients with avant-garde cancer.8 Likert scales ranging from 0 (disagree) to three (agree) are utilized for the analysis. Assessment items were determined past literature reviews and clinical familiarity with the patient population. Domains included in the calibration include self-consciousness, adjustment, sadness, anger, spirituality, and social support.viii Clinicians are encouraged to utilize this tool to place patients in need of more formalized clinical support.

| Table ane Assessment Tools for Anticipatory Grief |

The second tool, aptly named the "Anticipatory Grief Scale" (AGS), was developed to measure out the bereavement experience in female spouses of persons who received a diagnosis of dementia. The 27-item self-administered questionnaire assesses coping mechanisms and self-perceived reactions to impending loss.9 Similar the PGAC, Likert scales are used to clarify responses. Although originally developed for relatives of patients with dementia, other studies have modified the diction for use with other diseases; these modified scales have not been validated.11 The advantage of using AGS is that clinicians, social workers, and counselors tin can place the issues patients and family members are experiencing prior to death and then that proper interventions can have place to hopefully avoid long-term negative outcomes.11

The third tool, Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory, is a 50-item self written report calibration used to mensurate grief response of family caregivers of people with Alzheimer illness.10 This scale examines the personal sacrifices existence made by the caregivers, sadness and longing, and worry and isolation.10 This self-report produces a full grief scale, with higher levels of grief indicating anticipatory grief. This tool has been determined to exist valid and reliable in this population. A disadvantage of this tool is that it is specifically designed for caregivers and not patients (Table 1).

While there is no criterion-standard assessment tool to aid clinicians in differentiating between normal and pathological anticipatory grief processes,12 these tools are helpful in identifying patients and family members experiencing anticipatory grief. Additional research is needed to establish a well-validated measurement tool that is applicable to a wide diverseness of populations and easy to administer.

Direction OF ANTICIPATORY GRIEF

As previously mentioned, anticipatory grief tin can manifest equally a broad spectrum of physical, emotional, cerebral, and spiritual signs and symptoms.5 It is of import for providers to recognize the symptoms associated with anticipatory grief in guild to manage the experience and respond in an advisable and meaningful mode. Ideally, this would exist washed in shut collaboration with an interdisciplinary team including social workers and chaplaincy.

In a study published in 2011, Johansson and Grimby11 found that almost one-half the relatives of patients receiving palliative care sought the support of nurses. This finding reflects the importance of clinical staff readiness to answer to anticipatory grief. Nurses can expect the intensity of anticipatory grief to grow as the time of death nears, often requiring boosted support. The almost helpful back up is oftentimes delivered in the course of providing information regarding anticipatory grief, identifying and normalizing the experience, and addressing somatic concerns.half dozen Educational activity regarding somatic complaints may come in the form of slumber hygiene, nutritional guidance, or referrals to spiritual intendance. Nurses are essential in providing end-of-life care because of their dual roles as patient advocates and clinicians.6 Providing daily information and regular updates on the patient'due south condition reduces the anxiety of both patients and families. In addition to facilitating open advice, frequent and thorough updates can ease fears around patient suffering and offering families and caregivers peace of listen.vi

In addition, exploring past coping mechanisms with the individual and family volition provide information regarding previously constructive supportive measures and help to establish new coping abilities. It is important to evaluate for potentially harmful coping strategies, such as the reliance on alcohol, illicit substances, and other unhealthy behaviors.11

Attention to symptom control with a detail emphasis on pain management has been found to exist especially important. Nurses directly provide comfort-focused care and symptom management for this patient population, and they are aware of the importance of close monitoring for modifiable symptoms. In actively alleviating both patient and family unit suffering, the nurse offers a salubrious surround for the expression of anticipatory grief.

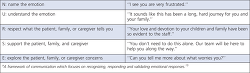

Utilization of specific communication strategies can be an additional tool to manage patients', families', and caregivers' anticipatory grief. Four effective advice strategies that hospice and palliative care providers can use are (1) ask-tell-ask, (2) NURSE statements, (3) "I wish" statements, and (iv) silent presence. The ask-tell-ask strategy is an invitation to the grouping or individual to talk almost current feelings and medical situations.xiii The NURSE framework focuses on recognizing, responding, and validating emotional responses of patients, families, and caregivers.xiii The NURSE acronym stands for (N) name the emotion, (U) empathize the emotion, (R) respect what the patient tells you, (Southward) back up the patient, and (Eastward) explore the patient's concerns (Table 2). "I wish" statements assistance to admit the difficult realities of the patient'southward prognosis every bit they grieve many losses-of health, changes in role identity, family construction, and independence.xiv When using such statements, "clinicians temporarily suspend their role every bit scientists and medical experts and respond as man beings faced with overwhelming circumstances that are non of their ain choosing."xv A final communication strategy is silent presence, which provides support and establishes space for determination making.16 Using these four communication techniques not only supports patients, families, and caregivers, but besides ensures them that their wellness intendance team volition not carelessness them (Table ii).

| Table 2 Toolbox of Communication Skills Nurse Statements |

CLINICAL SCENARIO

To illustrate how these techniques can be used, permit us revisit Mrs Jones, the 42-yr-old woman who received a diagnosis of metastatic chest cancer 4 years ago. Her oncologist has just left the room after speaking with her near the results of the computed tomography browse of her encephalon. Mary, her palliative care nurse, has known the patient from prior visits.

Nurse Mary enters Mrs Jones' room to find her crying and holding her head in her easily. Mary sits quietly at the patient'southward bedside and reassuringly places a hand on the patient'due south shoulder (silence). After a few minutes, Mrs Jones begins to speak:

Mrs Jones: "Dr Smith merely gave me bad news virtually my head CT (computed tomography) scan."

Mary: "Would it be helpful for us to talk virtually what Dr Smith told you?" (Ask-tell-ask)

Mrs Jones: "He told me the cancer has spread to my brain."

Mary: "Can you tell me more well-nigh what else he said?" (Explore argument)

Mrs Jones: "He said the cancer in my brain is what has been causing my headaches. My cancer is everywhere. There is no more handling for me. I am going to dice."

Mary: "I can only imagine how devastated you must feel." (Proper name argument)

Mary: "I wish the news was better for you and that we had better and stronger medicines for your cancer." ("I wish" statement)

Mrs Jones: "I thought I did everything I was supposed to do so that the cancer wouldn't spread. I am and so upset and shaken by this news."

Mary: "It sounds like this has been a long, hard journeying for you." (Understand statement)

Mrs Jones: "I wanted to beat this disease. I need more than time with my children and hubby. My children are just babies. They are only 10 and 12."

Mary: "Your love and devotion to your children and family have been evident since you began treatment. Y'all did everything yous were supposed to do." (Respect statement)

Mrs Jones: "I really wanted as much time as possible with my kids. Now I don't know what I should tell them-or even how and when to say information technology."

Mary: "I hear your concerns near your children and your hubby. You don't need to do this alone. Our team can help y'all." (Support argument)

Mrs Jones: "Thanks."

Mary: "Can you tell me more nigh your concerns about the children?" (Explore statement)

Mrs Jones: "I am really worried about how to pause this to the kids. I have only told them a little bit about my cancer since they are then immature. I didn't want to frighten them. Maybe that was wrong of me? Now I accept to tell them I am going to dice."

Mary: "Y'all know your children the best, and your arroyo was correct for them at that fourth dimension. At that place are many ways our team can help you and your family now that you have to explain this difficult news. Would yous like to hear more than about how nosotros may be able to help?" (Ask-tell-ask)

Mrs Jones: "Yes, okay."

Mary: "Our squad consists of your oncologist and oncology nurses, but also a specially trained social worker, massage therapist, fine art therapist, and chaplain. We will do everything we can to back up yous and your family (support statement). For example, our staff can help you share news with your husband if you lot would like. We tin can too plan with you and your husband about how to explicate the state of affairs to the children and make sure they get the support they need. Would these things exist helpful?" (Ask-tell-ask)

Mrs Jones: "Yes, I only felt so lone and overwhelmed this morn. I recall I feel a little bit improve knowing that you can help me effigy out how to suspension this to my family. Just I still simply tin't believe the cancer has spread so much, and there is no more therapy for me."

(Silence)

Mrs Jones: "I feel better knowing that you lot can help me speak with my family."

Utilizing these communication skills will let palliative care and hospice providers to optimize care and support for patients, families, and caregivers experiencing anticipatory grief.

Cardinal IMPLICATIONS FOR PALLIATIVE NURSING

Palliative care and hospice providers encounter patients, families, and caregivers experiencing anticipatory grief on a daily basis. Given this overwhelming exposure, it is essential for providers to have a clear understanding of anticipatory grief and the skills necessary to best support patients, families, and caregivers.17 Providers demand to exist able to identify those experiencing anticipatory grief by utilizing the various cess tools bachelor. Once those experiencing anticipatory grief are identified, providers tin can notice it useful to use various interventions and strategies. These interventions include identifying physical and psychological symptoms and treating them with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, providing support and instruction to patients, families, and caregivers, and utilizing empathetic communication strategies.

CONCLUSIONS

Further research and education highlighting nursing advice in a palliative intendance population would be beneficial. Nursing is the sole profession represented by the authors, posing a potential limitation of the commodity; a more than comprehensive approach would be to elicit social piece of work, chaplaincy, and physician perspectives as well.

References

Source: https://www.nursingcenter.com/ce_articleprint?an=00129191-201602000-00005